My Dearest passed away 4 months ago. According to the most recent statistics, over 2.6 million Americans die each year, with well over 600,000 of these deaths attributed to cancer. His death, 6 years following a diagnosis of an extremely rare form of pancreatic cancer, is neither shocking nor unexpected to anyone other than those who adored and revered him. He lived a full, happy, worthwhile life. He died with dignity and by his own choice. Rather than fighting an unexpected medical crisis that sideswiped us, was unsustainable, unwinnable, and guaranteed to destroy all quality of life, he chose to discontinue life-supporting glucose and slip peacefully into a coma leading to a quick death.

Robert was—in the words of good friend Betsy Quammen — “exemplary.”

We spent the last day of his life in the ICU at Bozeman Deaconess Hospital, reliving happy memories of events we shared in our 34 years together. Robert insisted we spend the day alone, calling no one, as he felt he had said everything he needed to say to others and he didn’t want his last hours filled with sadness and pleas for a different reality. His doctors agreed with his decision to accept his death sentence while admiring his courage. We laughed and cracked jokes rather than shedding tears, even when daughter Anya arrived unexpectedly and shared Robert’s final two precious hours of consciousness. Buoyed by Anya’s presence, he asked me to call son Sam. They spoke for a while, then Robert said, “I love you, Sam,” letting the phone fall into my hand. His eyes closed and he was gone.

Robert left me to navigate these deep channels and tsunamis of grief that accompany moving day-by-day through the fog of unending sorrow. He trusted me to figure out how to live beyond simple survival. I have come to respect the fluidity of grief and its ever-changing nature. I consider myself first and foremost a designer. I see what is before me and imagine different approaches, altered perspectives, or something entirely new. These past 4 months, engulfed in Robert’s screaming absence, I have realized there are subtle paths that have the possibility of softening the inevitability of crushing loss. There’s no escaping the pain, and the need for a process, but there are ways to make it less brutal.

A first step is a vital step: Acknowledge the person and what made their life worthwhile and their loss genuine. Talk about them and let their spirit and soul transition by keeping them alive within you. Robert was—in the words of good friend Betsy Quammen — “exemplary.” A true gentleman, he lived life according to well-worn manners and virtues that thankfully have survived modern culture: He stood when a lady entered the room and pulled back her chair at the table, he politely listened to another’s point of view — even when he found it disagreeable or full of half-baked truths. He rarely cursed, always sent thank you notes, asked people about their children and aged parents, remembered names, and knew how to turn a conversation to avoid arguments. He possessed a great curiosity about a variety of topics, with history, music, politics, and how to improve your golf game being the tip of a vast reservoir of knowledge. He had a near photographic memory, which constantly expanded due to incessantly reading non-fiction, of the type guaranteed to put me to sleep. He was a scholar, a musician, a man who smiled often, chuckled softly, and loved puns. He was generous, giving people the benefit of the doubt, trusting them until they proved themselves unworthy. He constantly questioned his place in the world and the future of Judaism. He studied the Torah, able to quote scriptures and knowledgeably discuss the subtle differences in translations and interpretations of both the Old and New Testament. Few people had any idea of the depth of his spirituality and that his deep-rooted core foundation was first and foremost being a Jew. He loved his children and family, was loyal to his friends and performed good deeds with no expectation of acknowledgment.

Robert died all too soon, leaving a void that expands with the passing of time. He was blessed with many gifts, but music is the one that most quickly comes to mind. He possessed an amazing talent and loved all kinds of music. He could hear a movie score and then sit down and play it by ear, many times embellishing and improving upon the original. Our home was filled with constant music, improvised, practiced, made for singing along, a solitary note emerging into a fluid song filling the air. Now the silence is deafening.

He was a scholar, a musician, a man who smiled often, chuckled softly, and loved puns.

Many books and articles have addressed the journey of losing a loved one. There are standard clichés: “Time heals all wounds,” “Don’t make any major decisions for a year,” “He’s in a better place.” There are the rituals, beginning with sympathy cards, casseroles, phone calls expressing shock and sorrow. I found myself thrown into the sisterhood of widowhood, and have a few observations and clichés I’d like to share. I’m sure with time I will have even more. But, for now, the first is the reality that no one can ever describe what you will feel and experience when you face the death of your soul mate, your parent, or child. It is so personal, visceral, immediate, and overwhelming that only you can own it. Those of us who are actively grieving need to be compassionate towards those who are blissfully ignorant of the journey. People and their reactions will surprise you.

No matter how expected, a loved one’s passing is a direct punch to the solar plexus. It knocks the air out of you, and along with the inability to breathe, it also erases short-term memory and the capacity to clearly reason and think. The combination of loss, longing, and incredulousness brings about a strong desire to exert some order and control to the chaos. So, at the time when you are least capable of making truly rational thoughts, you need to feel you are in charge. It is what reaffirms life and the enormity of death. The widow, the parent who has lost their child, the one inconsolably suffering, needs to feel they are moving forward with decisions and actions. There will be those who understand this and step forward at exactly the right moment, empowering you to carry on. Thankfully, my family and friends have given me strength while honoring my dignity over and over again. Blessings come in many forms.

Death is a numbing, shocking, and detailed process. It is filled with minutiae and legalities that involve unpleasant decisions ranging from financial matters to picking a funeral facilitator, whether you are embalming, burying, or cremating the body, what you dress the deceased in, the tenor of the service, when it is held, where the remains eventually end up, how many death certificates are required and who needs copies. Having a point person take charge of checking off procedural steps are advised. Diplomacy and gentle suggestions are preferable to mandates. I so appreciate those who helped guide me while letting me feel that I orchestrated the arrangements, even when they made the important decisions. They granted me a sense that I would be able to restore order to my life while supplying their strong shoulders to rely on. They resisted the urge to point out that I had discussed and decided upon who was speaking at the funeral five times already. They indulged me in my repetition of the story of Robert’s last days, as I searched for meaning beyond his loss. There is comfort in feeling the earth is not at a permanent tilt, and nailing down some basics helps anchor things.

Most of us understand social circles and how we fit within another’s life. Some circles overlap, while others are based on a specific activity or circumstance. We interact with close family, best friends, our casual lunch or fishing buddies, parents of our children’s friends, college roommates, travel companions, hairdressers, work partners, neighbors who say hi when we are fetching the paper, and even estranged friends we hope one day to resolve our differences with. We all have friends we hold near and dear even though we rarely connect. Circumstances keep us apart but we are still forever joined. Death affects everyone within our circles. It is a time we reflect on our own inevitable death and the fragility of life. Death requires the living to give and take–to allow others space and time to express their emotions, give voice to their regrets, to rejoice in their love and feelings of loss. One must forgive the stupid, clumsy comments people make during the awkwardness of raw emotions. A classic, for me, was a relatively good friend consoling me by wailing, “Oh, you’ll never love again! How will you survive, knowing you’ll always be alone!” I knew she meant that Robert was the love of my life, but her delivery needed a re-write.

Lives are meant to be celebrated, especially as they end. This takes planning. Weddings and death have a tendency of disrupting the social order in that some folks suddenly insert themselves in a position beyond their actual relationship. They grandstand, demanding attention, telling inappropriate stories, causing everyone to be uneasy as they talk far too long and mostly about them self. I don’t know if there is a way to minimize this or it is simply human nature. I witnessed my 90-year-old mother wanting to slap an octogenarian during a memorial service for my dad when the fellow droned on about things that just weren’t so. I finally stood up, thanked the guy, and offered a rousting toast to my mom that succeeded in shutting him down. Maybe we all need a “verbal bouncer” when this type of situation happens. It can be avoided, though, by someone coaching all designated speakers to stick to 5 minutes or less and share a unique remembrance that adds life and substance to the deceased.

There is an outpouring of emotion and support with someone’s passing. Time is distilled as activities happen in a flurry. The first few weeks are overwhelming. Then you face being alone. I’ve come to realize it would be far more meaningful and helpful to space things out over months rather than condensing things into days. My advice is for circles of family and friends to form “Support Groups” and band together to schedule phone calls, flower, and food deliveries, invitations to do things over the coming months. It is depressing to receive dozens of short-lived floral arrangements within a few days of your beloved’s passing. Your home is inundated, then, when everyone leaves after the funeral, you are left with dozens of dead floral arrangements and rotting food that compounds your depression. A better system is to pick a florist, have each participant write a touching card, sign everyone’s name to each card, and set up for the florist to deliver an arrangement and card once a month for a time period. Receiving an unexpected bouquet with a great card four months following your beloved’s death is a joy, along with being a game changer of knowing your friends are united in long-term support.

A true gentleman, he lived life according to well-worn manners and virtues that thankfully have survived modern culture: He stood when a lady entered the room and pulled back her chair at the table, he politely listened to another’s point of view — even when he found it disagreeable or full of half-baked truths.

People grieve in their own ways. Knowing the person who has lost their loved one, figure out what will engage them in life. Call with solid offers. “Let’s go see the new Merle Streep movie. I’ll pick you up at 5;30 and we’ll have dinner, then the movie.” Or, “It’s supposed to snow tonight. Let’s take the dogs snowshoeing tomorrow.” Devoted friends have let me turn down invitations, but they persist, finally putting their foot down and insisting we go out for dinner, go for a hike, or get manicures. Open-ended invitations or statements like, “Let’s get together,” do not fit the situation. When you are immersed in grief you tend to say no to anything with a wiggle room. Don’t provide a way out. Call and say, “I’m running errands. I’m grabbing lunch to go, so I’m getting you something and stopping by so we can eat together. You want a salad or a sandwich?” Have an action plan. My daughter brought two different groups of Kansas City girlfriends for 3-night trips. She didn’t ask permission, she just announced they were coming. How could I sit around and cry when my house was filled with social gossip, business ideas, discussions of dog breeds, and which designers had nailed it this season?

Travel is also good. Planning events and future activities help get through the loneliness and sadness that wants to snuff out the day. One girlfriend sent me information on a cruise and a special rate for a double room with a note saying, “We are going. You’ve always wanted to see St. Petersburg.” The trip is in June and I am excited. My son Lex announced that for his 30th birthday he wanted us to revisit the Pushkar Camel Fair in India. November is months from now, but just knowing it is happening keeps my spirits lifted. Seeing dates on the calendar help current sad days pass with fewer tears.

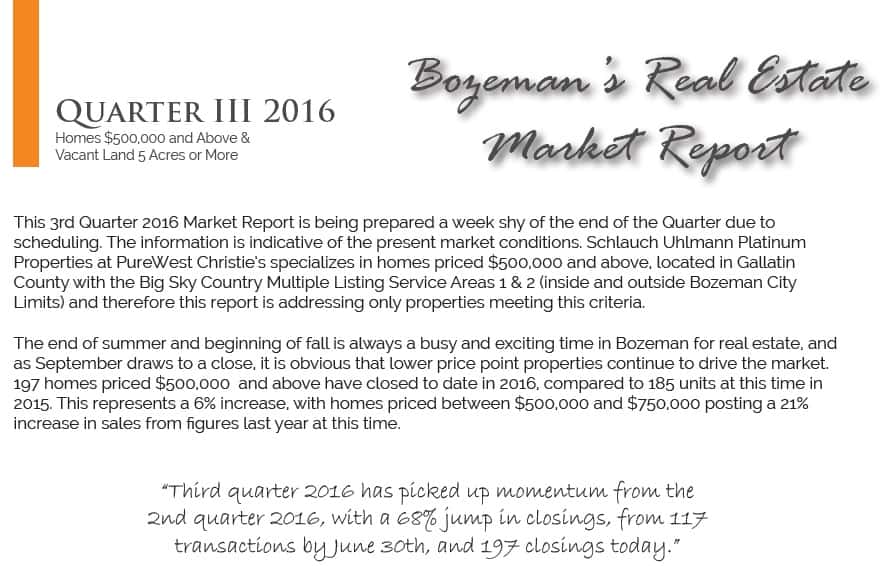

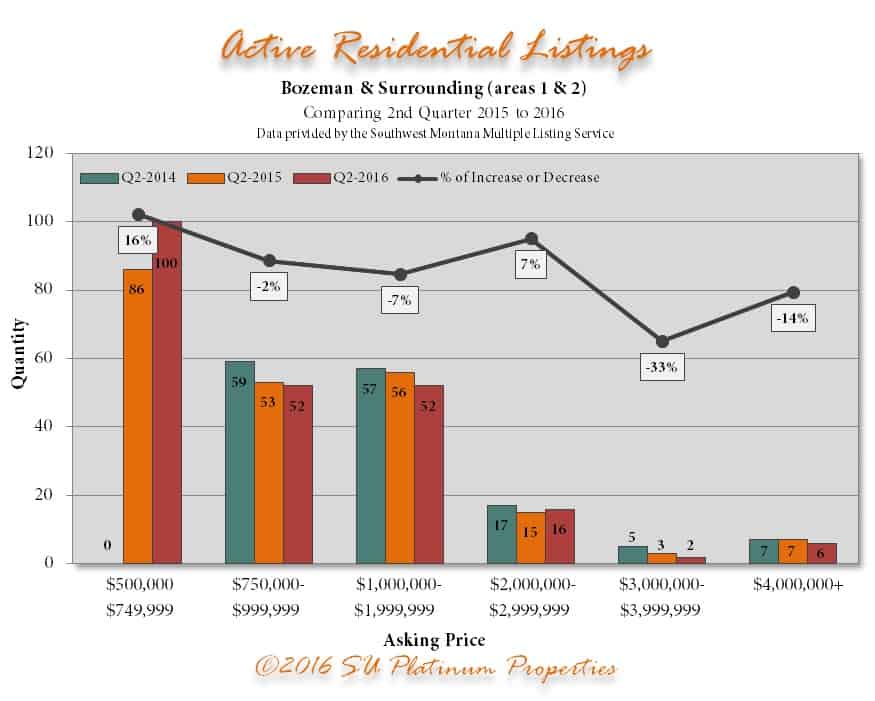

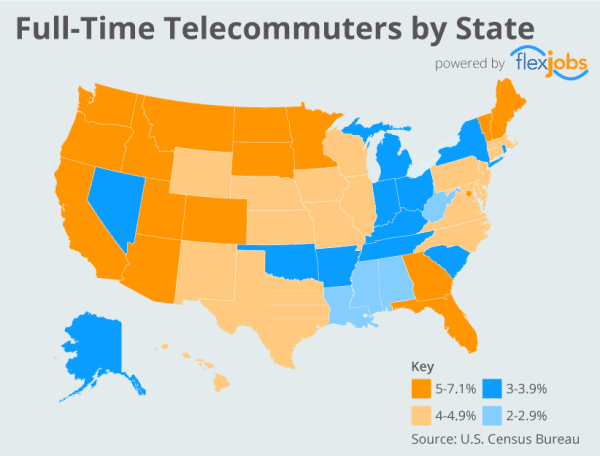

Work and routines are essential. I am very fortunate that I love my job. As a high-end real estate agent, I meet incredible people who dream of becoming Montanans and people who are ready for a new chapter in their life. Helping them navigate and make smart choices gives me a sense of accomplishment and pleasure. It occupies my time in a way that allows time to do its magic. I stick to a routine of getting up each day and having a list of chores and items I want to plow my way through. Keeping busy and having satisfaction at the end of the day that I made progress goes a long way in protecting mental health. You have to keep in motion or grief smothers out the light.

The details of transitioning a person from “Living” to “Deceased” goes on for months. And the wound is always raw. Robert’s name is still on our Amazon Prime billing and every month I wonder if it is time to inform accounting that he did not watch The Darkest Hour last week and no longer needs a list of future viewing. Each time I remove his name from a roster or account, it is as if he dies yet again. He diminishes. His shadow shrinks.

Me and My Love

The best gift of all is keeping the person alive in stories, tales, going through photos, reliving funny moments and foibles. Robert was quirky, oftentimes difficult, certainly no saint, but he was always loving and interesting! I am happy when he is part of the conversation when he is with us in spirit. Unexpectedly phone calls, texts, and letters that center on sharing some aspect of Robert, and how he impacted another’s life, cause my heart to swell. As a Jew, Robert felt this life was all there is and that his legacy is in his deeds, his children, his honoring of his ancestors. He touched many people from many different avenues of life and was a force of good, of positive affirmation, of optimism. I know I am the most blessed of people to have been his wife, the mother of his children, and always his soul mate. I look to him and my various circles to give me the strength to carry on. One passing day at a time. Final word on it: Death sucks.